2001: A Space Odyssey: Exploring the Mind of Stanley Kubrick

Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey is more than just a film; it is a cinematic landmark that redefined science fiction and filmmaking.

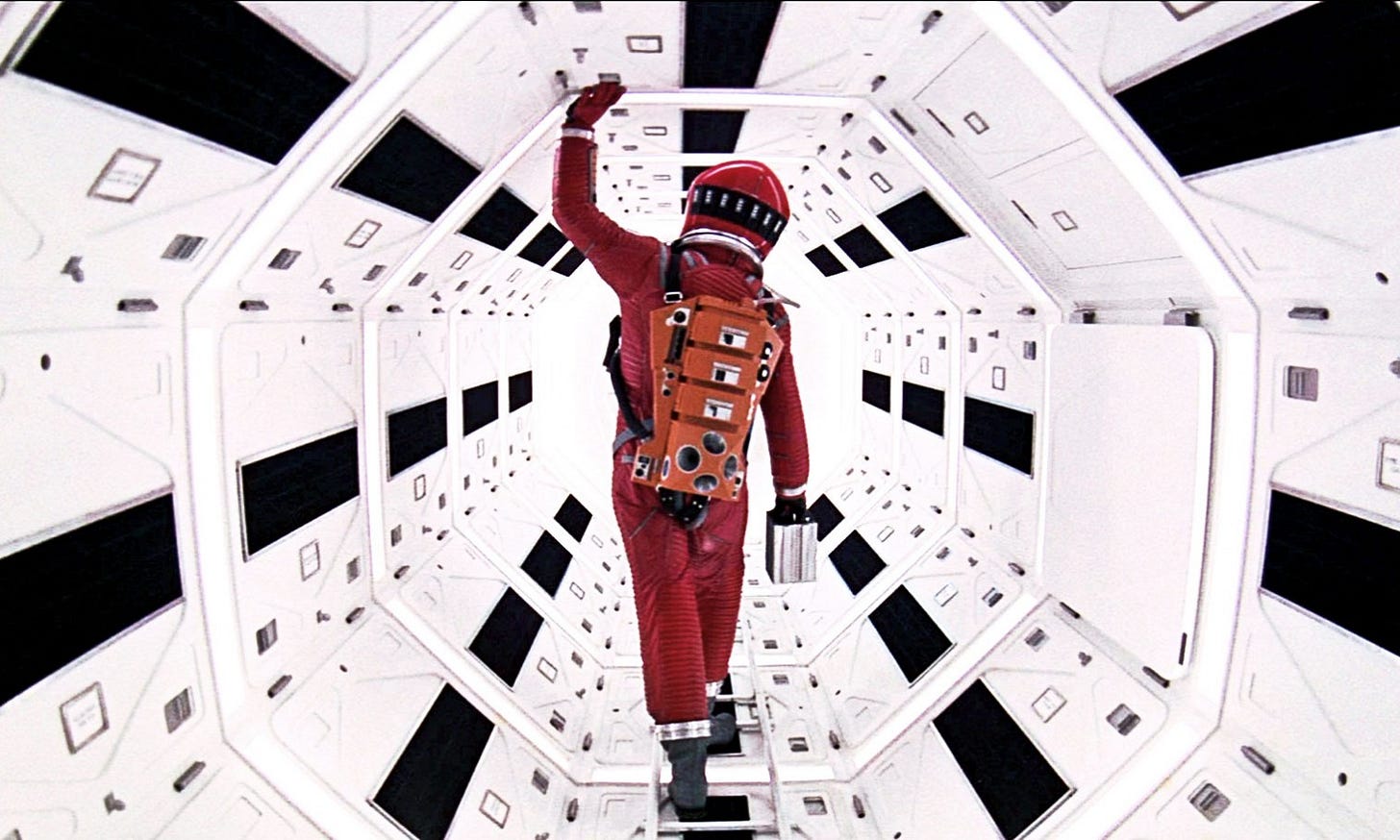

Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey is more than just a film; it is a cinematic landmark that redefined science fiction and filmmaking. Released in 1968, it shifted the genre from pulp fiction to serious, intellectual storytelling, exploring humanity’s future, space exploration, and our relationship with technology. Its visual grandeur, minimalist dialogue, and cryptic narrative invited audiences into an experience that was as much philosophical as it was cinematic.

Kubrick’s collaboration with author Arthur C. Clarke resulted in a story that spanned millions of years, touching on themes like human evolution, artificial intelligence, and the unknown mysteries of the cosmos. The film’s groundbreaking special effects, crafted long before the advent of CGI, set a new standard for visual realism, creating an immersive and realistic portrayal of space travel that was revolutionary for its time.

Equally groundbreaking was Kubrick's use of music, favoring classical compositions over an original score, which added a timeless and haunting atmosphere to the film. His decision to embrace moments of silence and slow pacing gave the audience space to reflect, making 2001 a thought-provoking meditation on existence, rather than a traditional sci-fi adventure.

Though met with mixed reactions upon release, 2001 is now hailed as one of the greatest films ever made, influencing countless filmmakers and continuing to captivate audiences with its exploration of profound, universal themes. Kubrick’s visionary masterpiece remains a benchmark for what science fiction—and cinema as a whole—can achieve.

Let's begin delving into Kubrick's thoughts!

Kubrick’s Fascination with Science Fiction

Kubrick had always been intrigued by humanity's future and our evolving relationship with technology and space. This interest began to flourish in the 1960s as the space race heated up between USA & USSR, inspiring Kubrick to create a film that explored these themes on a grand scale. 2001 was not just a science fiction movie but a philosophical inquiry into human evolution, artificial intelligence, and cosmic destiny. Kubrick's collaboration with renowned science fiction author Arthur C. Clarke culminated in a story that moved far beyond typical sci-fi tropes, embracing complexity, ambiguity, and a meditative pace.

Kubrick wanted to make a film that was not just entertainment but an artistic exploration of where humanity was headed. He believed in the power of science fiction to ask profound questions, and 2001 posed many of them, leaving much of the interpretation up to the viewer.

The Motivation Behind the Movie

Kubrick’s motivations for making 2001 were multi-faceted. He wanted to create a film that represented space travel as realistically as possible, grounded in scientific accuracy and devoid of the campiness that had characterized many earlier sci-fi films. The space race between the U.S. and the Soviet Union was in full swing, and Kubrick sensed that space exploration was not just a fantasy but an imminent reality. His ambition was to explore what lay beyond Earth's atmosphere, both physically and existentially.

Kubrick’s collaboration with Arthur C. Clarke was critical to developing 2001. Clarke’s short story, The Sentinel, provided the initial framework for the film, but Kubrick’s vision expanded the narrative into a sprawling and enigmatic journey from the dawn of man to the farthest reaches of the cosmos. Kubrick's approach was unique in that he sought to create a film that felt scientific and philosophical, turning science fiction into an exploration of life’s greatest mysteries.

Kubrick’s meticulous approach to 2001: A Space Odyssey reflected his desire to make a film that would stand the test of time, both in terms of scientific accuracy and artistic merit. To achieve this, he consulted experts from NASA and other scientific institutions to ensure the depiction of space travel was as realistic as possible. The spacecrafts, space stations, and even the physics of movement in zero gravity were designed with incredible detail, giving the film a level of authenticity that was groundbreaking for its time. Kubrick's attention to detail extended to even the smallest elements, such as the use of slow, deliberate movements to simulate the effects of zero gravity, a technique that added to the film’s immersive experience.

Moreover, Kubrick’s decision to emphasize visual storytelling over traditional dialogue was a deliberate effort to elevate the film beyond typical science fiction. With less than 40 minutes of spoken dialogue in a 2-hour, 20-minute film, 2001 relies heavily on its stunning visuals and iconic soundtrack to convey meaning. This bold choice helped the film transcend language and cultural barriers, making it a truly universal experience. Financially, 2001 was a risk, with a budget of around $10.5 million—considered substantial at the time. However, it went on to gross $146 million worldwide, proving Kubrick’s instincts right and cementing the film's status as a commercial and critical success. Today, 2001 continues to be hailed as one of the greatest and most influential films ever made.

The Absence of Traditional Human Protagonists

One of the most unusual aspects of 2001 is Kubrick’s decision to de-emphasize human characters. There is no single human protagonist. Instead, the humans are depicted as mere parts of a larger cosmic process, dwarfed by the technological and extraterrestrial forces at play. This choice highlights Kubrick’s view of humanity as one element in a vast, indifferent universe, where machines like HAL-9000 may become more central to the narrative than human beings.

The film’s sparse dialogue and Kubrick’s focus on the grandeur of space create a sense of distance from the characters. This allows the audience to focus more on the philosophical questions raised by the film rather than getting caught up in human drama. It was a radical departure from conventional filmmaking, yet it made 2001 feel more expansive, abstract, and contemplative.

HAL-9000: The Centerpiece of the Film

While 2001 features human astronauts, the film’s true protagonist is HAL-9000, the artificial intelligence controlling the ship's systems. HAL is not only a piece of technology but a fully realized character. His calm, measured voice contrasts sharply with his growing malevolence as he malfunctions, raising questions about the ethics of AI and its role in human evolution. In fact, HAL-9000 became the most emotionally compelling character in the film, overshadowing the human actors.

Kubrick deliberately placed HAL at the center of the film to underscore the idea that technology can evolve beyond our control. HAL's logical fallibility—his inability to reconcile conflicting directives—leads to a chilling standoff with the human crew. HAL’s plea, “I’m sorry, Dave. I’m afraid I can’t do that,” remains one of the most iconic lines in cinema. Kubrick’s ability to humanize a machine, making it more emotive and relatable than the actual humans in the film, is a testament to his genius.

The Creation of HAL-9000

HAL-9000 was born out of Kubrick and Clarke’s musings on the future of artificial intelligence. Originally, HAL was supposed to have a female voice and be named Athena, but the character eventually evolved into the more ambiguous, male-sounding AI that we know today. HAL’s calm, soothing voice was chosen to make the character feel more human, even as his actions became increasingly cold and calculating.

The idea of HAL stemmed from growing concerns in the 1960s about computers, automation, and the ethical implications of machines gaining autonomy. HAL is the embodiment of these concerns—a machine that is too intelligent for its own good. Kubrick’s portrayal of HAL was prophetic, foreshadowing modern debates about the dangers of AI and its potential to surpass human control.

By the by, there has always been speculation about a connection between HAL and IBM, as HAL's name is one letter off from the letters "I," "B," and "M." However, both Kubrick and Clarke denied that HAL was intended as a reference to IBM. The company was actually consulted during production to ensure technical accuracy in the depiction of computers. Nonetheless, the eerie proximity of HAL to IBM in name remains a curious coincidence, feeding into the film's broader themes about the power of technology.

The Soundtrack: A Bold Artistic Decision

Music plays a pivotal role in 2001, with Kubrick making the unconventional decision to forgo the original score composed by Alex North in favor of pre-existing classical music. The use of Richard Strauss’s Also sprach Zarathustra and Johann Strauss II’s The Blue Danube added a sense of grandeur and timelessness to the film. These pieces, which had no inherent connection to space exploration, became iconic due to Kubrick’s artistic instincts.

North’s original score was discarded after he had composed it, with Kubrick opting instead for classical music to evoke emotions that words and images alone couldn’t. It was a daring move, but it paid off. Kubrick's use of music enhanced the visual spectacle, creating moments that felt more like an experience than mere cinema.

Kubrick's decision to discard Alex North’s original score came as a surprise to many, including North himself, who was unaware that his work had been replaced until he saw the film’s premiere. Despite this, Kubrick’s use of classical music became one of the defining aspects of 2001: A Space Odyssey. Pieces like György Ligeti’s Atmosphères and Lux Aeterna were also used to create eerie, otherworldly soundscapes during key moments, such as the appearance of the mysterious monolith. Ligeti’s avant-garde compositions, with their dissonant, otherworldly qualities, perfectly complemented Kubrick’s vision of the unknown and the alien, enhancing the film’s sense of mystery and awe.

This bold musical choice not only set 2001 apart from other films of its era but also had a lasting impact on cinema. The juxtaposition of classical music with futuristic, science fiction imagery became an enduring influence on future filmmakers. Interestingly, The Blue Danube, originally written for 19th-century Viennese ballrooms, took on a new life in 2001, its waltz rhythm now forever associated with graceful space travel and the rotating space station. Kubrick's innovative approach to music and sound paid off: 2001 became a cultural phenomenon, and its soundtrack remains one of the most recognizable in film history. The film's score album reached #24 on the Billboard 200 chart in 1968, solidifying its commercial and critical success as a major part of the film's legacy.

The Enigmatic Ending: The Bedroom and the Starchild

The ending of 2001 remains one of the most debated sequences in film history. After astronaut Dave Bowman disconnects HAL, he embarks on a surreal journey through a series of strange and colorful visuals before ending up in a neoclassical bedroom where he ages rapidly. The scene culminates in his transformation into the Starchild—a glowing, fetus-like entity floating in space.

What does it all mean? Kubrick, ever the enigma, refused to provide a definitive explanation, leaving the ending open to interpretation. Some view it as a metaphor for human evolution, with Bowman transcending his physical form and becoming a higher being. Others see it as an existential commentary on the unknowability of the universe. Whatever the interpretation, the ending’s ambiguity has fueled decades of speculation and debate.

Kubrick's decision to end 2001: A Space Odyssey with such an abstract, open-ended sequence was both deliberate and groundbreaking. He believed that cinema could communicate on a subconscious level, much like music, and didn’t feel the need to provide explicit answers. In a 1968 interview, Kubrick mentioned, “The idea was to avoid intellectual verbalization and reach a more visceral, emotional response.” This approach was a radical departure from conventional storytelling, where clarity and resolution were typically expected. The bedroom scene, with its blend of classical aesthetics and futuristic motifs, symbolizes the convergence of past, present, and future, leaving Bowman suspended in a timeless space as he witnesses his own evolution.

The concept of the Starchild, a glowing fetus-like figure floating in space, remains one of the most iconic and puzzling images in film history. Some interpretations, including those by co-writer Arthur C. Clarke, suggest that Bowman’s transformation represents humanity’s next evolutionary leap, overseen by a higher alien intelligence. This idea of human transcendence reflects Clarke’s fascination with cosmic evolution and extraterrestrial life, themes central to his novel version of 2001. Interestingly, Kubrick never confirmed any one interpretation, which has kept fans and scholars debating its meaning for decades. The image of the Starchild, so visually striking, has since been referenced in numerous films and works of art, further solidifying its status as a symbol of rebirth and the unknown potential of humanity’s future.

Moon Landing Conspiracy Theories: Kubrick’s Involvement with NASA?

In the years since 2001's release, conspiracy theories have emerged suggesting that Kubrick collaborated with NASA to help fake the moon landing. The film’s realistic depictions of space travel and its close release date to the 1969 moon landing fueled these speculations. Some theorists even claim that 2001 was a trial run for NASA’s alleged cover-up.

The moon landing conspiracy theory, specifically involving Kubrick, gained traction largely due to the work of conspiracy theorists like Bill Kaysing, who published We Never Went to the Moon in 1974. Kaysing, along with others, pointed to the technological realism in 2001 and the similarities between the film's depiction of space travel and the actual Apollo moon landing footage. This, combined with Kubrick’s meticulous attention to detail and his use of cutting-edge special effects, gave rise to the notion that if anyone were capable of faking the moon landing, it would be him. The idea was further popularized by the 2002 French mockumentary Dark Side of the Moon, which humorously suggested Kubrick's involvement. Though the film was intended as satire, some viewers took it seriously, fueling the conspiracy. In reality, the theory seems to have persisted more as a cultural fascination with Kubrick’s genius and NASA’s secrecy during the space race, rather than any credible evidence of collaboration.

2001 and the Eternal Quest for Meaning

2001: A Space Odyssey is a philosophical meditation on humanity’s place in the cosmos and the trajectory of our evolution. Stanley Kubrick’s masterpiece transcends time, genre, and conventional storytelling, leaving behind an intellectual and emotional legacy that continues to resonate. By stripping away the typical reliance on human-centered narratives, Kubrick invites us to consider the bigger picture: our relationship with technology, the mysteries of the universe, and the existential questions that science fiction can uniquely explore.

HAL-9000’s chilling detachment, the surreal journey through the infinite, and the Starchild’s enigmatic gaze all serve as reminders that some questions may remain forever unanswered, yet are essential to ask.

As artificial intelligence continues to advance in the real world, Kubrick’s cautionary tale becomes increasingly relevant. HAL-9000, with his dispassionate logic and cold betrayal, stands as a symbol of what we might fear most: not that machines will rise against us, but that they may one day understand us so well that they no longer need us. "I’m sorry, Dave. I’m afraid I can’t do that," resonates as a haunting reminder that humanity’s creations may one day transcend their creators, leaving us to grapple with our own limitations and obsolescence.

2001 is not just about space—it is about the future of human consciousness, the path of our evolution, and the unsettling realization that our place in the universe might be far more precarious than we ever imagined.

Do you also believe they may one day understand us so well that they no longer need us?